Preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) is a very early method of prenatal diagnosis which was designed for couples who are at risk of transmitting an inherited disease to their children. More recently the PGD procedure has been used to help specific groups of infertile patients including older women, those with recurrent IVF failure or unexplained recurrent miscarriages. Such women are at an increased risk of producing embryos with abnormal chromosomes (aneuploid embryos). This modified PGD procedure is called Preimplantation Genetic Screening (PGS) and was previously known as ‘aneuploidy screening’ or PGD‐AS. For PGS, we examine several chromosomes in the embryo to determine how many copies there are. There should be two copies of each of these chromosomes in a normal embryo. The aim of PGS is to improve the pregnancy rate and to reduce the risk of miscarriage.

For us to carry out PGS you will have to go through routine in vitro fertilization (IVF) to generate multiple embryos to increase the chances of obtaining chromosomally normal embryos. In IVF procedures, to achieve a reasonable pregnancy rate, we usually transfer 2 embryos. We can usually only transfer a maximum of 3 embryos in women aged 40 years or more but after PGS the number is limited to two in this age group. It is important that you read the information leaflets on IVF.

Once the embryos have been generated, we perform the embryo biopsy procedure to remove 1 cell from each embryo for testing (see Figure 1). We usually do this on the morning of day 3 (3 days after the egg collection). Once the cells are removed, the embryos are returned to the incubator and the cells are prepared for the test. The embryo biopsy procedure has been shown not to harm the embryo. In fact, we know that up to half of the cells from the embryo can be lost without affecting the viability of the embryo.

We will use the technique of fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) to examine up to 6 pairs of chromosomes from the embryos (see Figure 2). The diagnosis takes up to 48 hours and so the embryos that are normal for the chromosomes examined can be transferred to the female patient the following day or the day after that. We are very familiar with this technique as it used routinely in the laboratory to test for chromosome abnormalities.

Preimplantation diagnosis was developed in the UK and the first cases were performed in 1989. Staff in the Genetics Department at University College London (UCL) have been performing PGD since 1991. The preimplantation genetic screening testing service is available in conjunction with the Human Genetics and Embryology Laboratory in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology. The first treatments in the UK for patients with chromosomal disorders and embryo sexing for X‐linked disease by FISH were developed by the team at UCL as well as those for many single gene disorders.

Problems that can occur during preimplantation genetic screening

Problems can occur during routine IVF treatment cycles for all patients:

- In some cases the woman does not respond well to the fertility drugs and the treatment cycle may be cancelled before the eggs are collected.

- Rarely, no eggs are found at egg collection.

- Occasionally eggs do not fertilize and there will be no embryos available for testing.

These problems are described in more detail in the IVF patient information leaflets.

Other problems are specific to the testing itself as follows:

- In some cases, after testing, all the embryos are found to have chromosome abnormalities, in which case there will be no embryos suitable for transfer. The greater the number of chromosomes screened the greater is the likelihood of finding chromosomal abnormalities.

- As women get older, they are more likely to have chromosomally abnormal embryos resulting in increased chance of miscarriage and the chance of a chromosomally abnormal baby (e.g., Down syndrome).

- Frequently, abnormal chromosomes are seen in some cells (chromosomal mosaicism) from preimplantation embryos of routine IVF patients. Mosaicism can cause problems for the diagnosis of chromosome abnormalities, because the cell we biopsy and test may not accurately represent the embryo. For this reason, PGS carries a slight risk of misdiagnosis (mainly due to chromosomal mosaicism).

- Since we are only screening for certain chromosomes, we recommend that patients consider undergoing prenatal diagnosis in the event of an ongoing pregnancy (this provides an analysis for all chromosome pairs).

- In the unlikely event that we should fail to obtain a diagnostic result on any of the embryos from a treatment cycle, after discussion with you, embryos for transfer would be chosen based on standard morphological assessment (i.e. those with the optimal cell number and least fragmentation).

- Even if surplus normal embryos are available, embryos that have been biopsied may not be suitable for freezing and used in a subsequent cycle.

- Despite PGS being performed, miscarriage may still occur.

Finally, we urge you to fully consider the financial costs of treatment and the emotional burden should a successful pregnancy not result following embryo screening for aneuploidy before undertaking a PGS cycle.

Fig. 1: Cleavage stage embryo biopsy.

An 8‐cell embryo is held in place while a single embryonic cell is removed for diagnosis (large arrow). The nucleus is visible in this cell (small arrow).

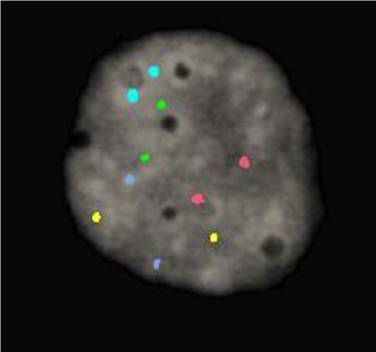

Fig. 2: Single nucleus following fluorescence in‐situ hybridization to determine chromosomal aneuploidy.

Two signals (normal number) of each color are seen in this cell indicating that it has a nearly 90% probability of being from a normal embryo. Chromosomes 13, 16, 18, 21 and 22 are represented by probes labelled in green, aqua, blue, red and gold respectively.